The Global Organ Shortage Crisis: Why Xenotransplantation Matters

The Transplant Waiting List Epidemic

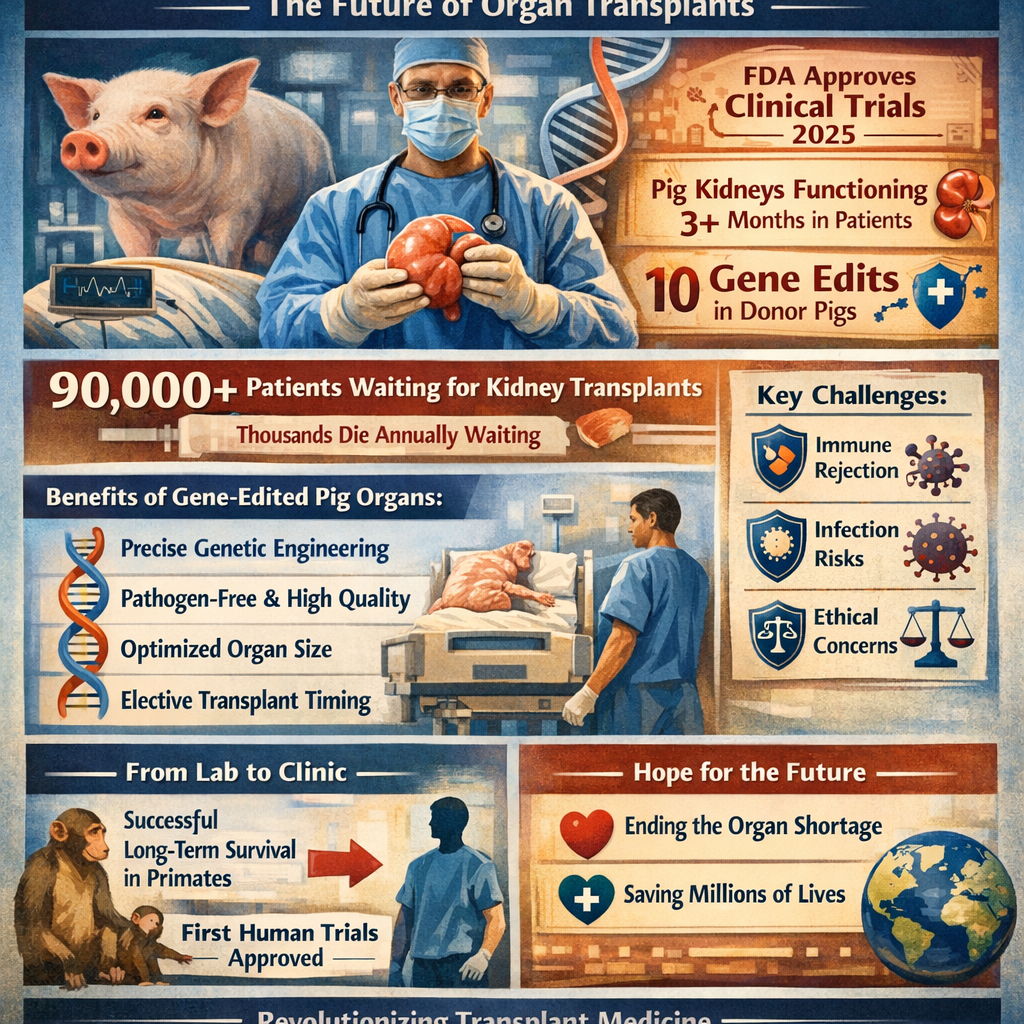

The most critical limitation facing transplantation medicine is the catastrophic shortage of donor organs relative to patient need. In the United States alone, more than 90,000 patients currently await kidney transplantation, yet only about one-third will ever receive a transplant during their lifetime. Globally, millions of people with end-stage organ failure lack access to life-saving transplantation, with thousands dying annually while waiting—a humanitarian crisis of staggering proportions.[1]

Current organ donation rates from deceased donors remain insufficient to meet demand despite presumed consent laws in many countries. This donor shortage reflects multiple barriers including declining brain death rates from improved trauma care and prevention, limited organ donation rates, family refusal of donation, and logistical challenges in organ procurement and allocation. Even in countries with the highest donation rates, substantial waiting lists persist for kidneys, hearts, livers, and lungs.[1]

Complications of Extended Waiting Times

The prolonged waiting times for transplantation impose extraordinary burdens on patients with end-stage organ disease. Patients awaiting kidney transplants endure lifelong dialysis—an exhausting treatment requiring 3-5 hours of blood filtration three to five times weekly, restricting diet, fluid intake, and quality of life. Patients awaiting heart, liver, or lung transplants often suffer progressive organ failure while waiting, with many deteriorating to the point where transplantation becomes no longer viable. Deaths on waiting lists represent only the most visible cost of organ shortage—the broader burden of disease, suffering, disability, and reduced life expectancy extends to millions awaiting transplantation.[1]

![]()

Xenotransplantation: A Solution to Organ Shortage

Defining Xenotransplantation and Its Promise

Xenotransplantation refers to transplantation of organs, tissues, or cells from one species (the donor) to another species (the recipient)—in this context, from genetically engineered pigs to humans. Unlike allotransplantation (transplantation between humans), xenotransplantation offers extraordinary potential advantages: unlimited supply of quality-controlled organs available on-demand, elective transplantation before patients become critically ill, elimination of waiting lists and associated morbidity/mortality, and potential for organs superior to human donations through genetic optimization.[1]

Why Pigs? The Biological Rationale

Pigs were selected as xenograft donors after decades of research evaluating multiple animal species, making them the most promising candidates for several compelling biological reasons:[1]

1. Anatomic Compatibility: Pig organ size and anatomy closely resemble human organs, enabling surgical transplantation using conventional techniques with minimal anatomic adaptation.[1]

2. Physiologic Function: Pig organs function similarly to human organs in terms of metabolic function, hemodynamics, and biological performance, making functional integration more likely than with evolutionarily distant species.[1]

3. Breeding Efficiency: Pigs reproduce rapidly, reaching adult size within six months, enabling reliable supply of transplantable organs without animal welfare concerns associated with nonhuman primates.[1]

4. Genetic Similarity: Pigs and humans share substantial genetic similarity—approximately 98% homology at key immunologically relevant loci—providing foundation for genetic engineering to enhance compatibility.[1]

5. Absence of Zoonotic Concerns: Unlike primates, pigs harbor few pathogens naturally infecting humans, substantially reducing xenozoonotic infection risk.[1]

Frontiers | Genetic engineering of pigs for ...

![]()

Genetic Engineering: The Critical Breakthrough

The Challenge: Multiple Barriers to Compatibility

The primary obstacle to xenotransplantation historically involved immune rejection occurring through multiple mechanisms including hyperacute rejection (occurring within minutes), acute rejection (within days), and chronic rejection (over months to years). Hyperacute rejection resulted from preformed natural antibodies (xenoreactive antibodies present in recipient blood) binding to xenoantigens—foreign carbohydrate structures on pig vascular endothelium—activating complement cascade and causing catastrophic thrombotic rejection within hours.[1]

These xenoantigens included α-gal (alpha-galactosyl) epitopes and other glycan structures recognized by human antibodies as foreign. The molecular basis of immune incompatibility derived from evolutionary divergence—pigs expressed molecules recognized as incompatible by human immune systems despite shared mammalian ancestry.[1]

CRISPR Gene Editing: The Solution

Revolutionary advances in gene-editing technology, particularly CRISPR-Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats), enabled precise genetic modification of pigs producing animals whose organs exhibited dramatically reduced immunogenicity and enhanced human compatibility. CRISPR-Cas9 technology enables precise editing of specific DNA sequences—"turning off" undesirable genes or "turning on" beneficial ones with unprecedented precision.[1]

The first generation of gene-edited pigs involved "knockout" modifications eliminating expression of xenoantigens: GGTA1 knockout eliminated α-gal epitopes, the primary target of preformed xenoreactive antibodies, while B4GALNT2 knockout eliminated Sda antigen—another important xenoantigen target. These knockouts substantially reduced hyperacute rejection risk.[1]

More advanced generations of genetically engineered pigs incorporated additional modifications including:[1]

· Knockout of CMAH gene: Eliminating another xenoantigen target

· Knockout of PERV (Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses): Eliminating risk of porcine retroviral infection in human recipients—a historically significant concern

· Knockout of growth hormone receptor (GHR): Controlling excessive organ growth that previously limited long-term xenograft survival

· Transgenic expression of human protective proteins: Including human CD55, CD46, and CD47 (complement regulatory proteins) that prevent complement activation, human EPCR (endothelial protein C receptor) and TBM (thrombomodulin) promoting anticoagulation, and human HO-1 (heme oxygenase-1) reducing inflammation

Frontiers | CRISPR technology towards genome editing of the ...

Gene Editing with CRISPR/Cas9 - Breakthrough in Genome ...

Current Gene-Edited Pig Generations

The United Therapeutics UKidney used in FDA-approved clinical trials incorporates 10 genetic modifications: four porcine gene knockouts (GGTA1, B4GALNT2, CMAH, and PERV inactivation) and six transgenic human genes (improving compatibility and reducing rejection). Alternative approaches include eGenesis's extensively modified pigs with 69 total genetic edits—59 knockout modifications eliminating endogenous retroviruses and 10 additional edits enhancing compatibility. These multi-gene modifications collectively create pigs whose organs are substantially more compatible with human immune systems.[1]

![]()

Clinical Achievements: Recent Milestones

Preclinical Successes in Nonhuman Primates

Before transitioning to human clinical trials, genetically engineered pig organs underwent extensive preclinical testing in nonhuman primates. These studies demonstrated remarkable organ survival: pig kidneys transplanted into baboons survived greater than 600 days (approximately 20 months) with one pig kidney achieving 900+ days of function. Pig heart xenografts in nonhuman primate recipients demonstrated survival exceeding 6 months in multiple cases—historically unprecedented achievement. These preclinical successes established sufficient proof-of-concept to justify human clinical application.[1]

In September 2021, the first-ever gene-edited pig organ was transplanted into a living human recipient at NYU Langone Health—a landmark moment initiating the clinical xenotransplantation era. This first transplant involved a pig kidney in a brain-deceased donor with a beating heart, followed by subsequent decedent studies confirming hyperacute rejection did not occur with gene-edited organs.[1]

In 2023 and 2024, pioneering compassionate-use cases transplanted gene-edited pig kidneys into living human recipients with remarkable results: One recipient who received a pig kidney in December 2024 maintained the xenograft functioning for greater than three months—exceeding all previous xenotransplant durations in living human recipients. Another recipient (in November 2024 at NYU Langone) received a 10-gene-edited pig kidney and returned home to Alabama, continuing to function until April 2025 when complications from an unrelated infection necessitated graft removal after over four months of function.[1]

FDA Approval for Clinical Trials

In a historic milestone, the FDA approved the first formal clinical trials of genetically modified pig kidney xenotransplantation in living human patients in 2025. The EXPAND trial (sponsored by United Therapeutics, beginning November 2025 at NYU Langone Health) represents the first formal clinical trial of UKidney xenotransplantation, initially enrolling six patients with expected expansion to 50 patients across multiple transplant centers. Parallel clinical trials include eGenesis's extensively engineered pig kidney program with FDA approval, expanding xenotransplantation testing to multiple genetic modification approaches.[1]

Kidney transplant surgery - Organ transplantation - NHS ...

![]()

Why Pig Organs Might Eventually Become Superior to Human Organs

Quality Control and Standardization

A revolutionary advantage of pig organ xenotransplantation involves the possibility of organs superior to those from human donors through genetic optimization and quality control. Unlike human donor organs—which vary substantially in quality depending on donor health, organ preservation time, and other uncontrollable factors—pig organs could be genetically standardized, quality-controlled, produced in optimal health, and procured under ideal conditions.[1]

Each pig could be raised in pathogen-free designated facilities (DPF—Designated Pathogen-Free), screened extensively for infectious organisms, monitored for genetic stability, and evaluated for optimal organ function before procurement. This systematic quality assurance would eliminate many variables causing human organ failure.[1]

Elimination of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

A critical advance enabling superior function involves organ preservation techniques preventing or minimizing ischemia-reperfusion injury—damage occurring when organs are deprived of blood supply during procurement, preservation, and transplantation. Recent 2025 research demonstrated that hypothermic machine perfusion (HMP)—continuously perfusing organs with cold, oxygenated preservation solution—prevents hyperacute rejection and maintains organ function despite prolonged cold ischemia. By utilizing HMP preservation, pig organs transported from distant procurement facilities tolerated five hours of cold ischemia without hyperacute rejection, enabling nationwide or international organ distribution.[1]

Human organs, conversely, are traditionally preserved via static cold storage (SCS)—simply cooling organs without active perfusion. The research demonstrating HMP superiority for pig organs suggests that optimized preservation could enable pig organs to function better than traditionally preserved human organs.[1]

Another potential advantage: genetically controlled organ size could be precisely matched to recipient body habitus. In human transplantation, donor-recipient size matching is constrained by available organs—sometimes requiring oversized or undersized organs suboptimally matched to recipients. With pig organ xenotransplantation, genetic modification of growth hormone pathways could produce organs in standardized sizes or even recipient-specific sizes, optimizing hemodynamics and function.[1]

Elective Transplantation Before Deterioration

Perhaps the most important advantage involves elective transplantation timing. Current human organ allocation prioritizes sickest patients (highest urgency scores), creating paradoxical situation where the most ill, medically compromised patients receive transplants when risk is highest. With xenotransplantation's unlimited supply, transplantation could occur electively—early in disease course when patients are healthier, comorbidities less advanced, and transplant outcomes optimized. Research indicates that earlier transplantation before patients deteriorate produces superior long-term outcomes, suggesting that xenotransplantation timing advantages could produce superior results compared to conventional transplantation.[1]

Customized Genetic Modifications for Individual Recipients

Looking forward, xenotransplantation could eventually enable recipient-specific genetic engineering. Rather than using universal gene-edited pig organs, customized modifications could target individual recipient's specific immune characteristics, HLA type, or genetic factors predicting transplant success. This precision medicine approach could create perfectly matched organs—potentially enabling long-term xenograft function without rejection, revolutionizing transplantation outcomes.[1]

![]()

Current Challenges and Remaining Barriers

Immune Rejection: Acute and Chronic

Despite remarkable progress in genetic engineering, multiple forms of immune rejection threaten xenograft survival. Hyperacute rejection (occurring within minutes to hours from preformed antibodies) has been largely controlled by genetic knockouts of major xenoantigens, but acute vascular rejection and antibody-mediated rejection remain significant threats.[1]

Antibody-mediated rejection involves xenoreactive antibodies (both preformed and induced) attacking the xenograft vascular endothelium, causing thrombosis, inflammation, and graft loss. The mechanisms remain incompletely understood, and optimizing immunosuppression to prevent this rejection while maintaining capacity to fight infection remains challenging.[1]

Chronic rejection, occurring over months and years, involves both antibody-mediated and T-cell-mediated immunity gradually destroying the graft. Long-term xenograft survival requires sustained immunosuppression that tolerates the organ while preserving immune function—a delicate balance not yet perfected.[1]

Infection Risk: Xenozoonosis Concerns

Xenozoonosis—transmission of porcine pathogens to human recipients—represents a theoretical risk that has dominated safety discussions around xenotransplantation. The primary concern involves porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV)—retroviral sequences integrated into the pig genome that theoretically could infect human recipients and potentially spread to close contacts. However, PERV transmission has never been documented in any human xenotransplant recipient despite decades of clinical experience, and newer generation gene-edited pigs (PERV-free) eliminate this risk entirely.[1]

Other potential infections include porcine viruses (cytomegalovirus, herpes viruses) and bacteria, though risk appears substantially lower than historically feared. Rigorous monitoring and xenozoonotic screening protocols mitigate infection risk.[1]

Optimal Immunosuppression Regimens

No consensus exists regarding optimal immunosuppressive therapy for xenotransplantation. Current approaches incorporate traditional immunosuppressants (calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate, corticosteroids) combined with novel agents including costimulation blockade (anti-CD154, anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies) and induction therapy.[1]

Finding the ideal drug combination maximizing xenograft acceptance while preserving immune function remains a critical research frontier. Some experts suggest that tolerance induction—enabling true immune acceptance rather than chronic immunosuppression—represents the ultimate goal.[1]

Frontiers | Novel portable hypothermic machine perfusion ...

![]()

Ethical, Social, and Regulatory Considerations

Xenotransplantation raises ethical questions regarding animal welfare and rights, particularly concerning raising pigs in contained facilities for organ procurement. While pigs in designated pathogen-free facilities receive specialized veterinary care exceeding conventional agricultural standards, questions persist regarding whether raising animals primarily for organ harvest raises ethical concerns.[1]

However, advocates note that extensive animal research occurs for pharmaceutical development and basic science, and that pig agriculture encompasses billions of animals globally—contextualizing xenotransplantation animal use as relatively modest if widespread clinical adoption occurred. Public engagement and transparent discussion of animal ethics remain important for social acceptance.[1]

Patient Selection and Informed Consent

Significant ethical challenges involve appropriate patient selection for early xenotransplantation trials. Initial clinical trials typically enroll older patients (55-70 years) with end-stage renal disease unlikely to receive human kidneys, facing either permanent dialysis dependence or death. For such patients, xenotransplantation may offer the only hope.[1]

However, informed consent requires patients understanding that xenotransplantation remains experimental with uncertain long-term outcomes, potential for rejection or infection, and unknown durability compared to human transplants. Transparent discussion of risks and uncertainty remains ethically essential.[1]

Successful xenotransplantation adoption requires public trust and acceptance. Survey research reveals that although many kidney disease patients express interest in xenotransplantation, substantial concerns persist regarding infection risk and graft function.** Public engagement, transparent communication of risks and benefits, and inclusion of diverse perspectives in xenotransplantation research will be essential for social license enabling widespread clinical adoption.[1]

![]()

The Future: From Experimental to Standard Care

Clinical Trial Expansion and Patient Population Growth

The FDA-approved clinical trials represent the beginning of a transformative transition from experimental laboratory studies to clinical standard care. As initial trials accumulate safety and efficacy data, regulatory pathways may enable expanded patient populations—younger patients, those with better baseline health, and broader organ types (hearts, livers, lungs in addition to kidneys).[1]

If current pig kidney xenotransplants demonstrate survival measured in years or more, regulatory approval may expand applications substantially. Successful one-year outcomes in clinical trials would represent historic achievement justifying broader clinical adoption.[1]

Technological Improvements: Machine Perfusion and Organ Preservation

Ongoing technological advances promise enhanced organ preservation and function. Normothermic machine perfusion (warm perfusion maintaining organ at body temperature) offers potential advantages over hypothermic perfusion, maintaining organ viability longer while enabling real-time function monitoring.[1]

Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications could enable predictive models optimizing organ preservation protocols, predicting rejection risk, and personalizing immunosuppression regimens. These advances promise to continually improve xenograft outcomes.[1]

Tolerance Induction: The Ultimate Goal

The ultimate objective in xenotransplantation research involves achieving immunological tolerance—genuine immune acceptance of xenografts enabling transplantation without chronic immunosuppression. Tolerance induction strategies including mixed chimerism (recipient immune cells tolerating both their own cells and donor cells) and thymic transplantation have shown promising results in nonhuman primates and may eventually enable tolerance-based xenotransplantation.[1]

If tolerance becomes clinically achievable, xenotransplantation could fundamentally transform transplantation—converting it from chronic immunosuppression-dependent therapy to one-time curative intervention with durable graft function approaching lifelong survival.[1]

![]()

Conclusion: Xenotransplantation as the Solution to Organ Shortage

Xenotransplantation—transplanting genetically engineered pig organs into human recipients—represents a transformative breakthrough with profound potential to solve the global organ shortage crisis and dramatically improve outcomes for millions suffering from end-stage organ disease. Remarkable advances in genetic engineering using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, clinical achievements demonstrating pig kidney function exceeding three months in living human recipients, and FDA approval for the first formal clinical trials represent historic milestones transitioning xenotransplantation from experimental science to clinical reality.[1]

Experts now credibly suggest that pig organs could eventually become superior to human donor organs through genetic optimization, quality control, elimination of infection risk, optimized organ sizing, and elective transplantation before patient deterioration. The unlimited supply of quality-controlled organs available on-demand promises to eliminate waiting lists, prevent deaths and suffering from organ shortage, and enable transplantation during optimal clinical windows maximizing long-term success.[1]

While significant challenges remain—including prevention of immune rejection, optimization of immunosuppressive regimens, and ethical considerations regarding animal use and patient selection—the trajectory toward clinical success appears clear and inevitable. Within the next 5-10 years, xenotransplantation will likely transition from experimental procedure to an established clinical treatment option available at major transplant centers. Within 20-30 years, genetically engineered pig organs may become a standard therapeutic approach for end-stage organ disease, fundamentally reshaping transplant medicine and providing life-saving therapy to millions.[1]

For the 90,000+ patients awaiting kidney transplants in the United States and millions more globally suffering from organ failure, xenotransplantation represents genuine hope—hope that technological innovation, scientific advancement, and clinical application might finally end the tragedy of organ shortage and enable everyone with end-stage organ disease access to life-saving, function-restoring transplantation. The future of transplantation may well be porcine.[1]

![]()

Citations:

PLOS ONE - A data-driven analysis of patient selection for xenotransplant human clinical trials (2025); Wiley - Clinical Xenotransplantation of Gene-Edited Pig Organs: A Review of Experiments in Living Humans (2025); Wiley - How Much Will a Pig Organ Transplant Cost? Preliminary Estimate (2024); Frontiers Partnerships - Contributions of Europeans to Xenotransplantation Research (2025); Wiley - Advances in Subclinical and Clinical Trials and Immunosuppressive Therapies in Xenotransplantation (2025); Wiley - Transplant Patients' Perceptions About Participating in First-in-Human Pig Kidney Xenotransplant Trials (2024); Wiley - Pathologic findings in preclinical and early clinical kidney xenotransplantation (2025); Nature - Hypothermic machine perfusion prevents hyperacute graft loss in pig-to-primate kidney xenotransplantation (2025); Frontiers - Recent progress in pig-to-human kidney xenotransplantation (2025); Wiley - Ethical Issues Involved in Solid Organ Xenotransplantation (2025); PMC - 2025: Status of cardiac xenotransplantation including preclinical models (2025); PMC - The current issues of translating clinical xenokidney transplantation (2025); PMC - The Time Has Come (2024); PMC - Genetically-engineered pig-to-human organ transplantation: a new beginning (2022); PMC - Xenotransplantation: past, present, and future (2017); PMC - Xenotransplantation Literature Update July-December 2024 (2024); PMC - Justification of specific genetic modifications in pigs for clinical organ xenotransplantation (2019); PMC - Progress toward Pig-to-Human Xenotransplantation (2022); Kidney.org - Clinical Trials for Pig-to-Human Kidney Transplantation Are Here (2025); NYU Langone - First Gene-Edited Pig Kidney Transplant Clinical Trial Begins (2025); PMC - Genetically Engineered Porcine Organs for Human Transplantation (2022); CDC - Xenotransplantation: Risks, Clinical Potential, and Future Prospects (2010); Kidney Fund - FDA greenlights first clinical trials for genetically modified pig kidney transplants (2025); Harvard Medical School - In a First, Genetically Edited Pig Kidney Is Transplanted (2024); NMJI - Progress towards Clinical Pig Organ Xenotransplantation (2025); PMC - Progress in xenotransplantation: overcoming immune barriers (2022); ScienceDirect - Xenotransplantation overview (2025)[1]

Post your opinion

No comments yet.