Framing the Question: Art, Ideology And Propaganda

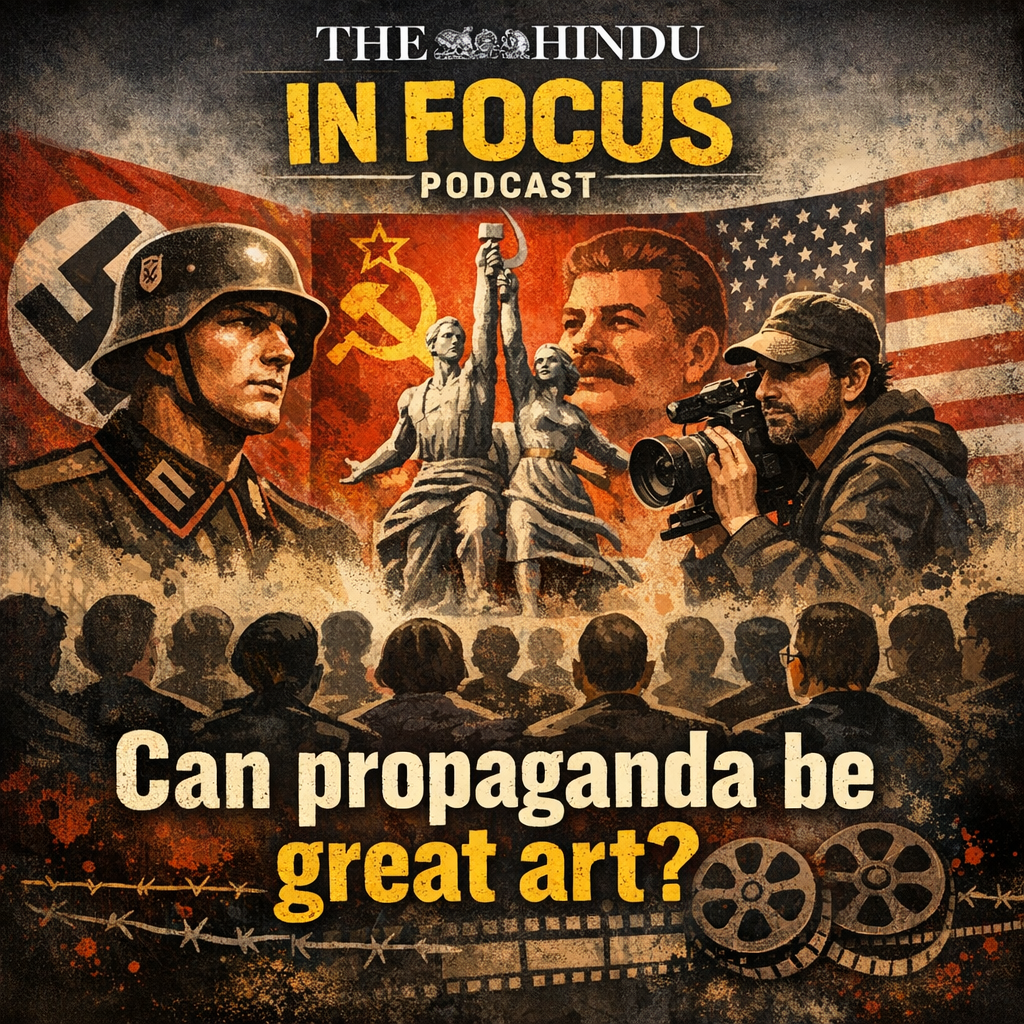

The episode starts by posing the core dilemma: can works created primarily to persuade or mobilise—rather than to explore, question or play—still count as great art. The hosts and guests anchor the discussion in classic examples: Nazi and Soviet films, political posters, and state-sponsored artworks that were technically sophisticated yet morally compromised.[1][2][6][7][8]

Drawing on George Orwell’s idea that “all art is propaganda,” the discussion notes that every artwork carries values and worldviews, but propaganda narrows this down into a single, insistent message. The question then becomes not whether art is political, but whether a work’s political purpose suffocates its ambiguity, nuance and openness—the qualities usually associated with artistic greatness.[9][3][10][5]

Mohanlal - IMDb

![]()

Historical Propaganda Cinema: Nazi And Soviet Experiments

The episode looks at 20th‑century propaganda cinema as a crucial testing ground for the debate. Nazi Germany treated film as a powerful tool for shaping consciousness, commissioning grand epics and carefully crafted features that embedded antisemitism, militarism and Aryan supremacy into compelling narratives and visuals.[6][4][7][11]

Soviet montage directors like Eisenstein and Vertov likewise saw no contradiction between art and propaganda; for many of them, cinema was meant to be tendentious and explicitly political. Their films pioneered montage techniques, radical editing, and experimental visual rhetoric that deeply influenced world cinema, even as they served a tightly controlled ideological project. This raises the central paradox: can formally innovative, historically important works still be admired as art when their purpose was to glorify oppressive regimes.[4][5][12]

![]()

Aesthetics Of Propaganda: Power, Craft And Epistemic Flaws

Philosophical work on propaganda, which the episode draws on, suggests that propaganda art is best seen as a subcategory of political art, marked by its rhetorical aggressiveness and “epistemic flaws.” Such works simplify reality, suppress inconvenient truths, and emotionally pressure audiences toward predetermined conclusions, even when they display great technical skill.[2][5]

The guests point out that propaganda can be visually arresting, musically powerful and narratively gripping, precisely because it exploits all the tools of art to close down doubt and complexity. From fascist posters celebrating war and mechanised violence to cinematic glorifications of national community, the artistry often serves to make harmful ideas more seductive, not more interrogable. This is why many critics remain uneasy calling such works “great,” even if they are undeniably important or influential.[3][10][11][2]

![]()

Modern Echoes: Contemporary Political Cinema And Campaign Imagery

The conversation then shifts from historical regimes to the present, noting that propaganda has not disappeared; it has simply adapted to new media ecosystems. Films, trailers, political biopics and even streaming shows can carry tightly coded ideological messages about nationalism, religion or security, while still claiming to be “just entertainment.”[13][14][15][8]

The episode references how contemporary films and promotional materials sometimes embed Islamophobic or majoritarian narratives in glossy, high‑budget packages, blurring the line between commercial cinema and political persuasion. Social media amplifies these images and clips, turning them into endlessly shared micro‑propaganda that can be aesthetically polished yet deeply polarising. The key question remains: when form is dazzling but content is manipulative or exclusionary, how should critics and audiences judge the work.[16][17][15][13]

Top hits and flops at Box Office 2025: Dhurandhar, Saiyaara ...

![]()

So, Can Propaganda Ever Be “Great” Art?

The episode does not offer a simple yes‑or‑no answer, but suggests several criteria for thinking about greatness in propaganda art. Works that acknowledge complexity, allow space for interpretation, and resist reducing people to stereotypes stand a better chance of being taken seriously as art, even when they have clear political commitments.[1][2][18][10]

By contrast, art that demands emotional submission, erases dissenting perspectives, and deliberately distorts reality in service of domination is harder to celebrate, no matter how technically accomplished it may be. The hosts conclude that museums, critics and viewers can—and should—study propaganda works for their historical and aesthetic significance, but must always keep their violent or oppressive contexts in view. In that sense, propaganda can be powerful, influential and even formally brilliant, yet still fall short of the ethical and imaginative openness many associate with truly great art.[2][3][10][5]

Post your opinion

No comments yet.