Recent research in Earth and Space Science reveals that understanding forest growth requires integrating multiple theoretical frameworks and modeling approaches that account for the complex interactions among environmental factors, physiological processes, and resource allocation strategies in plants. A comprehensive analysis of forest modeling demonstrates that distinct model clusters exist with varying degrees of process integration and complexity, ranging from individual tree and stand-level models to large-scale terrestrial ecosystem models. The research highlights critical trade-offs between model detail and scalability, revealing that forest science must balance sophisticated process representations with practical applicability for management and climate prediction. The study identifies key theoretical frameworks—including Functional Balance theory, Local Determination of Growth, and Optimality Principles—that provide the conceptual foundation for understanding how trees and forests allocate limited resources and respond to environmental change.[1]

Forest Modeling: Bridging Theory and Practice in Ecosystem Science

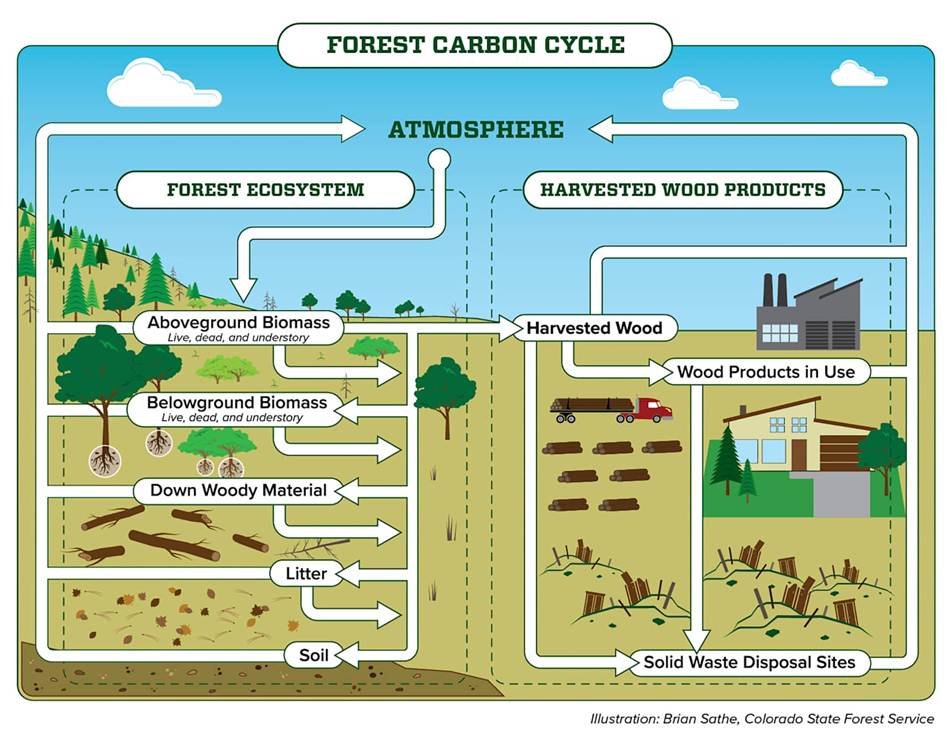

Forest modeling has emerged as an essential tool for understanding how trees grow, how forests develop, and how ecosystems respond to environmental stresses and climatic changes. Forests represent critical components of global biogeochemical cycles, carbon sequestration systems, and biodiversity repositories, making accurate understanding of forest dynamics essential for climate science, resource management, and environmental conservation.[2][3]

Global patterns and climatic controls of forest structural ...

The Challenge of Forest Complexity

Forests are inherently complex systems characterized by multiple interacting processes operating across temporal scales ranging from minutes (photosynthesis) to centuries (succession) and spatial scales from individual leaves to continental regions. This complexity arises from several factors:[2][3]

· Structural heterogeneity: Forests contain trees of vastly different ages, sizes, and species

· Physiological interactions: Competition, facilitation, and resource sharing among individual trees

· Environmental variability: Spatial and temporal variations in climate, soil, water, and light

· Ecological processes: Recruitment, growth, mortality, and succession occurring simultaneously

· Human management: Silvicultural treatments, harvesting, and other anthropogenic disturbances

Managing this complexity requires theoretical frameworks that simplify reality without losing essential mechanisms driving forest behavior.[3][2]

The Modeling Approach: Translating Theory into Prediction

Forests science is fundamentally integrative: understanding climate and water processes is as critical as understanding plant physiology for comprehending forest dynamics. This integrative nature has led to the development of diverse modeling approaches, each representing different compromises between biological realism and practical manageability.[2][3]

Models range across multiple dimensions of complexity:[3][2]

· Spatial scale: From individual trees to continents

· Process detail: From single-process focus to integrated ecosystem simulation

· Temporal resolution: From daily to multi-decadal time steps

· Species representation: From monoculture to diverse mixed-species forests

· Management integration: From purely ecological to management-focused applications

Key Theoretical Frameworks Driving Forest Growth

Functional Balance Theory: Resource Allocation as a Governing Principle

Functional Balance theory proposes that trees allocate carbon and nutrient resources among roots, stems, and foliage in response to environmental resource availability. The underlying principle suggests that plants maximize growth by maintaining balanced proportions of biomass that capture different limiting resources.[1]

Frontiers | Leaf nutrient traits of planted forests ...

Plant carbon allocation in a changing world – challenges and ...

In environments where water is limiting, trees invest disproportionately in root systems to access subsurface water. In nutrient-poor soils, trees invest in roots to forage for nutrients. In shaded understories, trees invest in foliage to capture scarce light.

This dynamic allocation mechanism means that forest structure and biomass distribution are not fixed but rather continuously adjust to match environmental opportunities and constraints. Models incorporating Functional Balance theory predict that:

· Trees growing in wet environments develop shallower root systems than those in dry environments

· Nutrient-poor soils select for deep-rooting species and increased root:shoot ratios

· Shaded positions favor trees with high leaf area index and extended foliage

· Resource-rich environments favor rapid, efficient growth with balanced proportions

Local Determination of Growth: Competition and Neighborhood Effects

Local Determination of Growth recognizes that individual tree growth depends critically on the local competitive environment created by neighboring trees. Rather than assuming that growth depends primarily on absolute environmental conditions, this theory emphasizes that competitive interactions with nearby neighbors fundamentally shape growth trajectories.[1][4]

Neighborhood Competition Mechanisms

A tree's growth rate depends on:[4]

· Light availability modified by neighbors: Taller neighbors create shade, reducing light for subordinate trees

· Water competition: Neighboring roots compete for soil water, reducing water availability

· Nutrient cycling: Decomposition and nutrient uptake in the immediate neighborhood affect nutrient availability

· Facilitation effects: In harsh environments, neighbors may provide protection from extreme conditions

· Spatial arrangement: The pattern of neighbor positions affects competitive intensity

This theoretical perspective explains why identical species in different neighborhoods show dramatically different growth rates, and why stand structure emerges from competitive interactions rather than being predetermined by site quality alone.[4]

Optimality Principles: Evolutionary Constraints on Resource Allocation

Optimality Principles propose that plants have evolved allocation strategies that maximize fitness (reproductive success) given environmental constraints. While natural selection operates on reproductive success rather than biomass production, optimality approaches provide useful mathematical frameworks for predicting allocation patterns.[1]

Optimality Framework Applications

Optimality approaches have generated predictions about:[2][1]

· Optimal leaf area: The amount of foliage that maximizes net carbon gain while managing hydraulic and structural costs

· Optimal root depth: The soil depth that optimally balances water acquisition against root construction costs

· Optimal reproduction investment: The allocation to seeds versus structural growth

· Optimal branch architecture: Branching patterns that optimize light capture while minimizing structural costs

These optimality-derived predictions have been validated against field observations in diverse forest types, suggesting that evolution has generated allocation solutions approaching theoretical optima.[1]

Forest Model Classification: Complexity and Process Integration

The research reveals that forest models cluster into distinct categories with characteristic levels of complexity and process integration.[1]

Frontiers | Modeling climate-smart forest management and ...

Stand-Level Growth Models: Simplicity and Management Utility

Stand-level models (e.g., 3-PG, 3-PGmix) represent forests as cohesive units characterized by average tree properties, total biomass, and stand-level productivity metrics. These models sacrifice individual tree detail in exchange for computational efficiency and manageability.[2][5]

3-PG Model Characteristics:

· Represents entire stands as single units

· Predicts stand productivity based on physiological principles

· Incorporates radiation interception, water balance, and carbon allocation

· Operates at monthly temporal resolution

· Successfully applied across diverse forest types globally

· Recent development of 3-PGmix extension allows simulation of mixed-species forests

Stand-level models excel for:

· Forest management decision-making

· Predicting productivity under different management scenarios

· Regional-scale assessments

· Integration with remote sensing data

· Long-term climate change impact projections

Individual-Tree Models: Capturing Structural Heterogeneity

Individual-tree models simulate each tree as a distinct entity, tracking its growth, competition with neighbors, and eventual death. These models capture the structural complexity and spatial variability inherent in real forests.[1][6]

Advantages of Individual-Tree Representation:

· Explicit competition: Direct representation of tree-to-tree interactions

· Structural heterogeneity: Can produce realistic tree size distributions

· Spatially explicit: Allows representation of specific forest spatial patterns

· Management simulation: Can represent selective harvesting, thinning, and other spatial treatments

HETEROFOR Model Example:

Recent validation of HETEROFOR demonstrated that spatially explicit, process-based models successfully predict short-term growth (5-16 years) of multiple species at both individual tree and stand levels, offering robust performance for structurally complex forests in eastern North America.[6]

Terrestrial Ecosystem Models: Continental and Global Scale

Terrestrial Ecosystem Models (TEMs) represent forests as components of continental or global-scale biogeochemical cycles, integrating multiple ecosystem processes including carbon, nitrogen, and water cycling.[1]

· Operate at coarse spatial resolution (grid cells of 1+ km²)

· Simulate multiple ecosystem types (forests, grasslands, deserts, etc.)

· Integrate with global climate models for Earth system simulations

· Predict ecosystem responses to global climate change

· Generate estimates of carbon sequestration and release

Scaling Challenge: Converting detailed process understanding from stand-level to continental scales requires aggregating individual-tree-level details into functional types or simplified representations that preserve key ecosystem behaviors while remaining computationally tractable.

Process Integration: Trade-offs Between Detail and Scalability

A key finding of the forest modeling analysis is that different model structures represent fundamentally different compromises between mechanistic detail and practical scalability.[1]

Colorado forests are releasing more carbon than they capture ...

The Detail-Scalability Trade-off

More detailed models that represent individual trees or multiple nutrient cycles produce superior predictions at small spatial scales but become computationally intractable at larger scales. Conversely, highly simplified models operate efficiently at continental scales but miss important process details affecting predictions in specific contexts.[1]

This creates a crucial tension in forest science:[2][3]

· Research context: Scientists often need process detail to understand mechanisms

· Management context: Forest managers often need practical, fast predictions

· Policy context: Policy makers need estimates of carbon sequestration or timber productivity at regional scales

· Climate context: Climate modelers need forest representations that integrate into Earth system models

Model Complexity Across Application Domains

The optimal model complexity depends critically on application:[1]

For Local Management Decisions:

· Individual-tree or fine-scale stand models preferable

· Detail enables representation of specific silvicultural treatments

· Can incorporate local site conditions

· Predictions for 5-50 year timeframes

For Regional Assessment:

· Stand-level models or aggregated ecosystem models appropriate

· Balance between detail and computational efficiency

· Can be parameterized with forest inventory data

· Predictions for 50-100+ year timeframes

For Global Climate Modeling:

· Simplified ecosystem modules required

· Must integrate smoothly with atmosphere and ocean models

· Functional type approach (grouping diverse species into categories)

· Predictions for climate change over centuries

Remote Sensing Integration: Modern Forest Monitoring

Contemporary forest modeling increasingly integrates remote sensing data to improve parameterization and validation across spatial scales.[3][8]

Mapping and Monitoring Soil Moisture in Forested Landscapes ...

Remote Sensing for Forest Characterization

Remote sensors provide cost-effective, high-resolution characterization of forest attributes across landscapes, overcoming limitations of traditional field-based sampling:[3][8]

· Optical sensors: Vegetation indices (NDVI, EVI) indicate greenness and productivity

· LiDAR systems: Three-dimensional representations of forest structure, canopy height, tree spacing

· Radar systems: Penetration through clouds enables monitoring in tropical regions

· Spectral analysis: Automated classification of forest types and condition

Process-based models increasingly harness remote-sensing data for:[9][10]

· Calibration: Using satellite estimates of LAI (Leaf Area Index), FAPAR (Fraction of Absorbed Photosynthetically Active Radiation), or canopy water content

· Validation: Comparing model predictions with independently-derived satellite estimates

· Scaling: Using high-resolution satellite data to characterize local site conditions for model parameterization

· Monitoring: Detecting changes in forest structure and productivity over time

3-PGS model exemplifies this integration, using satellite-derived vegetation indices to spatially parameterize forest productivity estimates across regions, enabling regional assessments with stand-level mechanistic detail.[2]

Carbon Cycling and Climate Change Implications

Forest growth models provide critical tools for understanding and predicting forest responses to climate change, including changes in productivity, mortality, and carbon sequestration.[1]

Introduction to Forest Carbon | Oklahoma State University

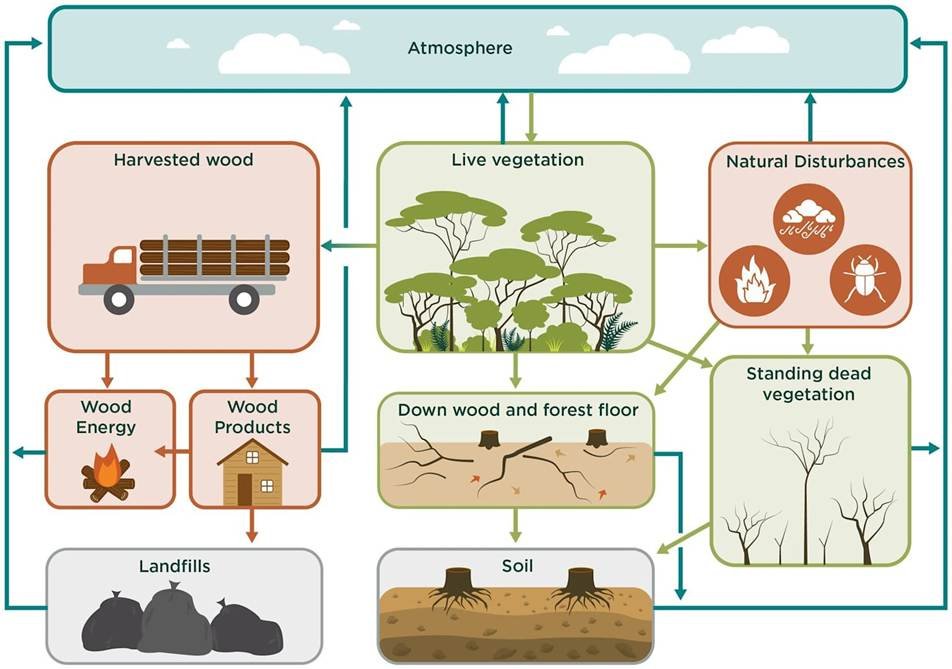

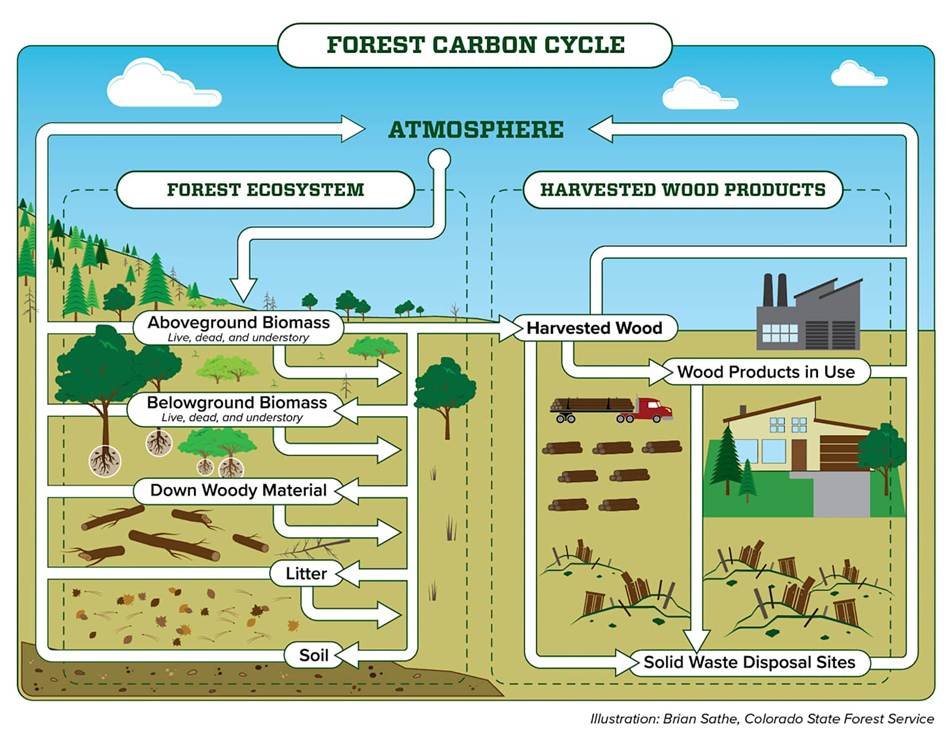

Forest carbon cycling involves multiple processes that models must represent:

Colorado forests are releasing more carbon than they capture ...

How Do Forests Sequester and Absorb Carbon? - Musim Mas

· Gross Primary Production (GPP): Total photosynthetic carbon fixation

· Respiration: Carbon losses through plant respiration

· Net Primary Production (NPP): GPP minus respiration; available for growth and storage

· Decomposition: Carbon release from dead biomass

· Disturbance impacts: Sudden carbon losses from fire, insects, harvesting

Process-based models simulate these fluxes mechanistically, allowing prediction of how climatic changes affect carbon sequestration capacity. Models demonstrate that:

· Warmer temperatures may increase growing season length, favoring growth

· Increased CO₂ may enhance photosynthesis (CO₂ fertilization)

· Drought stress may reduce growth and increase mortality risk

· Earlier snowmelt may alter seasonal water availability

Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment

Models enable assessment of forest vulnerability to specific climate scenarios, allowing identification of:[1][2]

· Regions where productivity may decline due to increased drought or temperature stress

· Shifts in species distributions as climatic envelopes move geographically

· Increased disturbance susceptibility from bark beetles, fire, or pathogens

· Carbon release risks from forest dieback or increased mortality

Future Directions: Advancing Forest Modeling

Several research frontiers promise to advance forest modeling in the coming decades.[1]

Novel Species Combinations and Climate Scenarios

Current forests often represent specific combinations of species under particular climatic conditions. Foresters frequently need predictions for novel situations—different species combinations, new climatic conditions, untested silvicultural treatments. Models must extend beyond "fitting" to historical data to making credible predictions for genuinely novel situations.[5]

Integrated Management and Ecosystem Services

Future models increasingly will integrate multiple ecosystem services—timber production, carbon sequestration, biodiversity support, watershed protection, recreation—allowing assessment of trade-offs and optimization of management for multiple objectives.[1][3]

Machine learning approaches are beginning to complement mechanistic models, using satellite data and field observations to identify patterns in forest structure and growth that may improve or replace traditional model parameterizations.[11][8]

Permafrost and Boreal Forest Dynamics

Boreal forests and permafrost represent critical climate feedback systems. New models incorporating permafrost dynamics and soil organic layer effects promise improved predictions of boreal forest responses to climate change, with implications for global carbon cycling and climate feedbacks.[12]

Conclusion: Forest Modeling as Integrative Science

Forest growth modeling exemplifies how complex biological systems can be understood through integrating multiple theoretical frameworks and mathematical representations of differing complexity. The recognition that distinct model clusters exist, each with characteristic advantages and limitations, suggests that no single "best" model exists; instead, model selection should depend on specific research questions and management objectives.[1][2][3]

The trade-offs between model detail and scalability reflect fundamental challenges in translating mechanistic understanding into practical predictions across spatial and temporal scales relevant to decision-making. As forests face unprecedented climate change and humans demand multiple ecosystem services, forest modeling tools that integrate mechanistic understanding with practical applicability become increasingly valuable.[3][1]

Future advances will likely involve greater integration of remote sensing, machine learning, and multi-scale modeling approaches that preserve mechanistic detail where necessary while remaining computationally tractable for larger-scale assessments. By continuing to advance forest modeling while remaining grounded in ecological theory and empirical validation, the science can provide increasingly reliable guidance for sustaining forest ecosystems and the critical services they provide in a rapidly changing world.

Post your opinion

No comments yet.