Understanding Ultra-Processed Foods: Definition and Classification

What Are Ultra-Processed Foods?

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are industrial formulations manufactured through extensive processing that deconstructs whole foods into component parts, modifies them chemically, and recombines them with numerous additives, often containing little to no whole food content. These products are engineered specifically for hyperpalatability, convenience, and extended shelf-life rather than nutritional value. UPFs typically contain high levels of added sugars, unhealthy trans fats, sodium, and artificial additives including colorants, flavor enhancers, and preservatives.[1][2]

Common examples of UPFs consumed widely in India include carbonated soft drinks, packaged biscuits, instant noodles, processed meat products (sausages, nuggets), flavored breakfast cereals, ready-to-eat frozen meals, sugary snacks, and confectionery items. These products dominate retail shelves and are aggressively marketed, particularly targeting children and adolescents through multiple channels.[3]

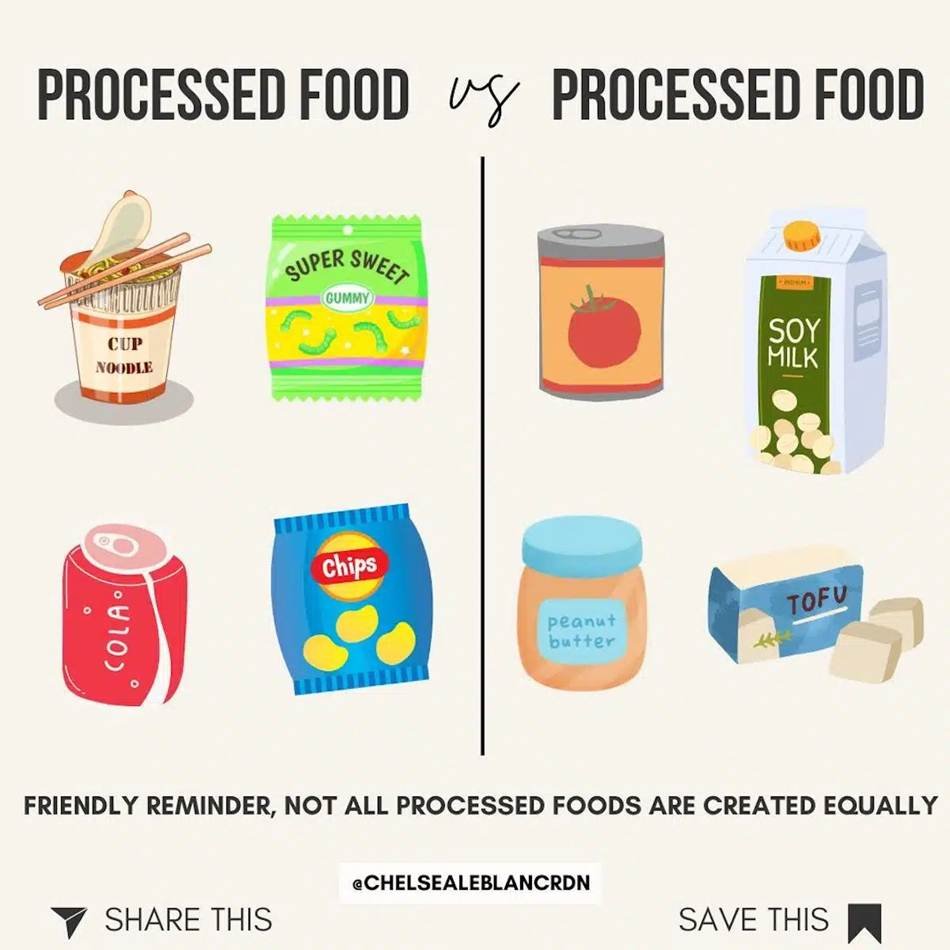

Processed Foods vs. Whole Foods: What a Dietitian Wants You ...

The NOVA Classification System

To standardize the identification of UPFs globally, researchers employ the NOVA classification system, which categorizes foods into four groups based on the extent and purpose of processing:[1]

Group 1 - Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods: Foods that undergo no significant alteration or only minimal processing through washing, drying, grinding, freezing, or pasteurization. Examples include fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and fresh meat. These foods retain their original nutritional profiles without added chemicals.

Group 2 - Processed Culinary Ingredients: Substances extracted and purified from Group 1 foods or obtained from nature through pressing, refining, grinding, milling, or drying. These include oils, fats, sugar, salt, honey, and vinegar—used in cooking and food preparation but rarely consumed alone.

Group 3 - Processed Foods: Created by adding Group 2 ingredients to Group 1 foods, primarily to increase shelf-life or improve palatability. Processing includes fermentation, baking, pasteurization, or canning. These foods retain recognizable forms of original foods and contain limited ingredients. Examples include canned vegetables, cheeses, and freshly baked whole grain bread.

Group 4 - Ultra-Processed Foods: Industrial formulations combining ingredients rarely found in household kitchens, including substances derived from further processing of foods (hydrogenated oils, high-fructose corn syrup) and various additives (colorants, emulsifiers, colorants, flavor enhancers, and preservatives). These foods are engineered to be hyper-palatable, convenient, and ready-to-consume, with minimal to no whole food content.

![]()

The Rapid Rise of Ultra-Processed Food Consumption in India

Market Expansion and Sales Growth

India's ultra-processed food market has experienced unprecedented growth, reflecting broader nutritional transition patterns associated with urbanization, rising incomes, and globalization of the food system. According to recent research published in The Lancet, India's UPF retail sales surged from $0.9 billion in 2006 to nearly $38 billion in 2019—a 40-fold increase representing the fastest growth rate globally. This explosive expansion signals a fundamental shift in India's food consumption patterns.[4]

50 Unhealthiest Snacks on the Planet

Urban-Rural Disparities and Demographic Trends

While urban areas have historically driven UPF consumption due to greater availability and marketing penetration, the food industry is rapidly expanding into rural markets. Urban Indian households purchase significantly higher quantities of UPFs compared to rural counterparts, with categories including sweet snacks and ready-to-eat foods showing consistent growth between 2013 and 2016 across all demographic clusters. The demographic group most vulnerable to aggressive UPF marketing includes children, adolescents, and lower-income populations who are increasingly exposed to convenience foods and packaged snacks as urbanization accelerates.[5]

![]()

Ultra-Processed Foods and India's Non-Communicable Disease Burden

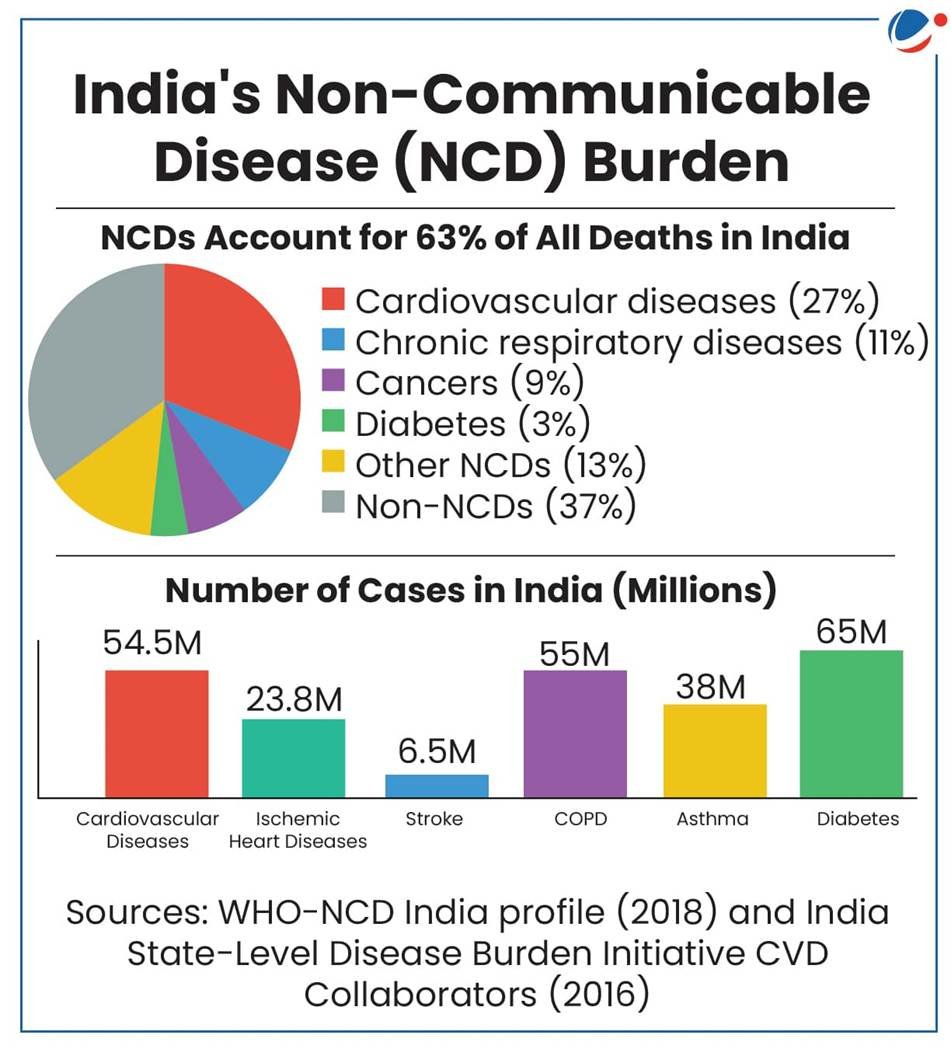

India faces a rapidly escalating public health crisis of non-communicable diseases, with millions suffering from preventable chronic conditions. According to the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (2016-2018), more than half of children and adolescents (5-19 years old) had biomarkers indicating substantial NCDs risk burden. The major NCDs affecting India include cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, certain cancers, respiratory diseases, and obesity-related conditions—all strongly associated with unhealthy dietary patterns rich in ultra-processed foods.[6]

Global data reveal that NCDs account for 74% of all deaths worldwide, with the burden disproportionately affecting developing nations including India. Economic and social consequences extend beyond individual health impacts, straining healthcare systems and reducing productivity across the population.[7]

Specific Health Impacts: Obesity, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease

The rise in UPF consumption has coincided with dramatic increases in obesity prevalence across India. Obesity rates among men have doubled from 12% to 23%, while women's rates increased from 15% to 24%. In urban areas, obesity prevalence reaches crisis levels, with approximately one in four Indians now classified as obese, and one in three experiencing abdominal obesity—a particularly dangerous form of excess weight that increases visceral fat accumulation around vital organs.[4]

Approximately one in ten Indians (10%) currently suffer from type 2 diabetes, positioning India among nations with the highest diabetes burden globally. UPF consumption directly contributes to diabetes development through multiple mechanisms involving rapid blood glucose elevation, insulin resistance, and metabolic dysfunction. Children exposed to high UPF diets during critical developmental periods face significantly elevated risks of early-onset diabetes.[4]

Cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, and stroke, account for a substantial portion of India's NCD-related mortality and represent a leading cause of premature death. UPF consumption increases cardiovascular disease risk through mechanisms including elevated sodium intake, unhealthy fat accumulation, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction.[8]

Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) | Current Affairs | Vision IAS

![]()

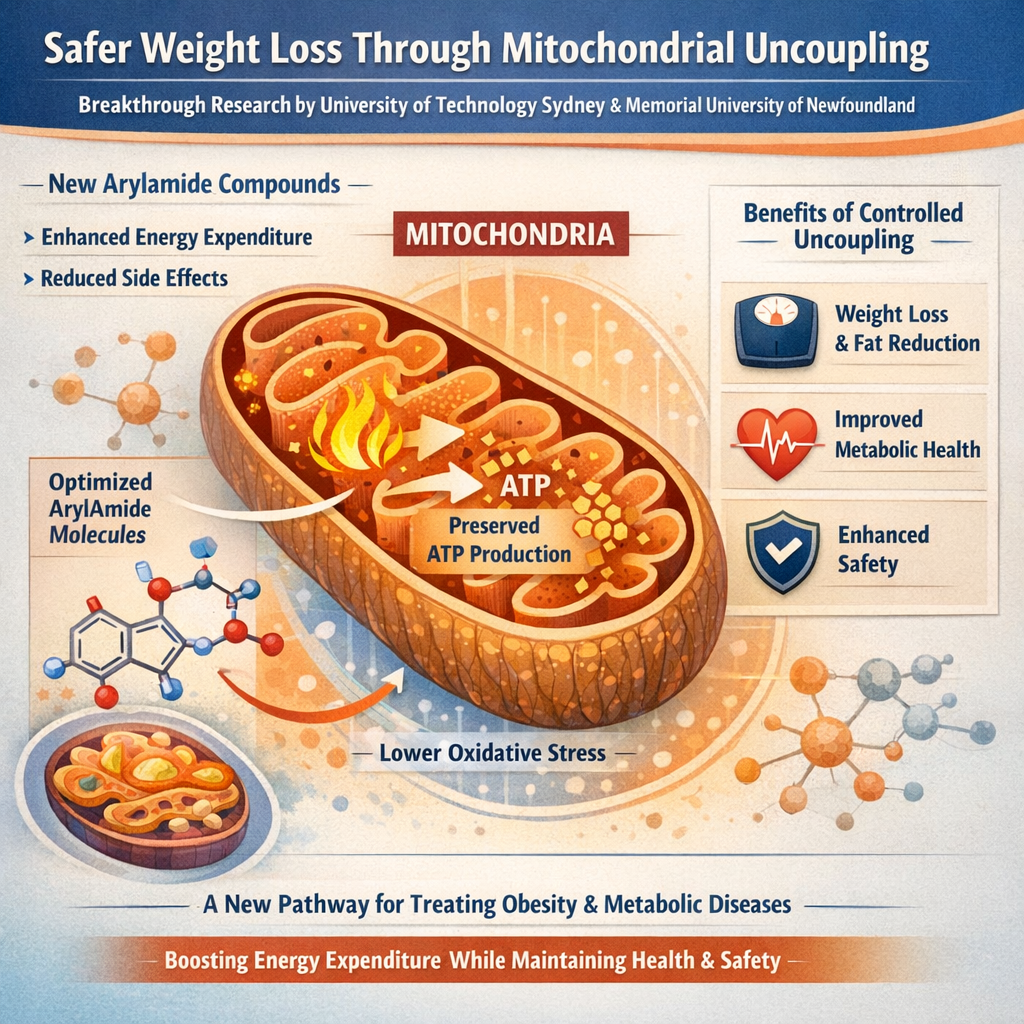

How Ultra-Processed Foods Fuel NCDs: Biological Mechanisms

Metabolic Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance

UPFs promote metabolic dysregulation through multiple pathways. These foods are characteristically high in refined sugars and unhealthy fats while being low in dietary fiber, leading to rapid blood glucose and insulin spikes that stress the pancreas and reduce insulin sensitivity over time. This repeated metabolic stress initiates a cascade toward type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. The absence of fiber in UPFs eliminates satiety signals that normally communicate fullness to the brain, promoting excessive caloric overconsumption.[2]

Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Additives, preservatives, and specific nutrient imbalances in UPFs trigger chronic low-grade inflammation—a foundational process underlying cardiovascular disease, cancer, and metabolic disorders. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) naturally formed during UPF processing accumulate in the body, promoting oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine release. Research demonstrates that UPF consumption increases biomarkers including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, both associated with increased NCD risk.[9]

The lack of dietary fiber and presence of artificial additives in UPFs harm beneficial gut bacteria, reducing microbial diversity and promoting dysbiosis—a condition linked to systemic inflammation, depression, and metabolic disease. A disrupted microbiome increases intestinal permeability (leaky gut), allowing bacterial lipopolysaccharides to enter circulation and trigger immune activation and chronic inflammation throughout the body.[2]

UPFs often contain chemical additives functioning as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormonal regulation. Emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and chemicals from food packaging (such as bisphenol A and phthalates) can disrupt metabolic hormones and stress response pathways, contributing to metabolic syndrome and obesity. These effects are particularly concerning in children during critical developmental windows when hormonal programming occurs.[2]

While energy-dense, UPFs paradoxically promote micronutrient deficiency. A notable decrease in potassium, magnesium, and vitamins A, C, D, E, B12, and B3 occurs with increased UPF consumption, alongside zinc and phosphorus deficiency. This nutritional paradox—excess calories paired with insufficient essential nutrients—creates conditions for metabolic disease while promoting weight gain.[2]

whole foods vs processed foods — Healthy Habit HHI

![]()

Vulnerable Populations: Children, Adolescents, and Lower-Income Groups

Marketing Targeting and Health Implications

Aggressive and pervasive marketing of UPFs targeting children and adolescents fosters preference for unhealthy foods during critical taste-preference formation periods, establishing lifelong dietary patterns. Television advertisements, digital media, school promotions, and celebrity endorsements normalize UPF consumption. Research demonstrates that children exposed to UPF marketing display increased purchase requests and consumption, with effects particularly pronounced in lower-income households with limited access to healthier alternatives.[10]

Developmental and Cognitive Impact

Maternal and child consumption of UPFs high in saturated fats and added sugars may inhibit cognitive development, with associations observed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, learning disorders, and motor developmental delays. Longitudinal studies show that children with higher UPF consumption at age three display elevated blood lipid concentrations by age six—early indicators of cardiovascular disease risk.[2]

School kids worldwide are more obese than ever. Can we ...

![]()

Policy Framework and Regulatory Responses in India

Current Indian Policy Landscape

India has documented recommendations through a national multisectoral plan of action to prevent and control NCDs, including proposed front-of-pack labels and advertising bans, though implementation remains incomplete. Key policy gaps include:[10]

· Lack of uniform definitions for UPFs in Indian regulatory frameworks

· Inconsistent terminology (junk foods, fast foods, ready-to-eat foods, processed foods, packaged foods, HFSS foods) complicating policy application

· Insufficient enforcement of existing advertising restrictions targeting children

· Absence of taxation mechanisms on sugar-sweetened beverages and UPFs

Global Policy Models and Evidence

Countries including Mexico and Hungary have successfully implemented taxes on sugary beverages and snack foods, with Mexico's sugar-sweetened drink tax associated with reduced purchase and consumption, offering a validated model for reducing UPF intake. Economic analysis suggests taxation increases prices and reduces consumption, particularly among price-sensitive populations.[2]

Front-of-Package Warning Labels

Chile's adoption of front-of-package warnings for foods high in sugar, sodium, calories, and saturated fats has demonstrated effectiveness in guiding consumers toward healthier choices, with research showing these labels significantly impact purchasing behaviors. India's proposed front-of-pack labeling system could similarly empower consumers to identify and avoid high-risk products.[2]

The United Kingdom and Brazil restrict UPF advertising, particularly during children's programming, reducing young viewers' exposure to persuasive marketing. Such restrictions are critical in India where children's media consumption is rapidly increasing.[2]

Dietary Guidelines and Public Awareness

Brazil and Canada have incorporated explicit recommendations to reduce UPF consumption in national dietary guidelines, favoring fresh and minimally processed foods, alongside public health campaigns raising awareness about UPF health risks. India requires similar comprehensive public education initiatives.[2]

![]()

Recommended Policy Interventions for India

Addressing India's UPF-driven NCD burden requires coordinated action across multiple sectors:

1. Regulatory and Legislative Action

· Implement and enforce front-of-pack warning labels on foods high in sugar, sodium, and unhealthy fats

· Introduce taxation on ultra-processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages with revenue directed toward nutrition education

· Restrict UPF advertising during children's programming and in schools

· Establish clear regulatory criteria for identifying and labeling UPFs using standardized classification systems

2. Public Health and Education

· Launch national mass awareness campaigns highlighting UPF health risks and promoting whole food consumption

· Integrate nutrition education into school curricula emphasizing food processing concepts and label reading

· Train healthcare providers to counsel patients on reducing UPF intake

· Support community-based nutrition programs in high-risk populations

3. Food Industry Engagement

· Encourage voluntary product reformulation reducing sugar, sodium, and unhealthy fat content

· Support development and marketing of healthier food alternatives

· Restrict marketing expenditures promoting UPFs, particularly targeting vulnerable populations

4. Food Environment Modifications

· Implement school food policies restricting UPF availability in canteens and vending machines

· Subsidize fresh produce in underserved urban and rural areas

· Support development of local food systems and traditional food promotion

5. Research and Surveillance

· Establish national dietary surveillance systems tracking UPF consumption trends

· Fund research identifying effective intervention strategies in Indian contexts

· Monitor implementation and health outcomes of policy interventions

![]()

What Consumers Should Know: Individual Action Steps

While policy changes are essential, individuals can reduce health risks through practical dietary modifications:

Read Food Labels Carefully: Examine ingredient lists and nutrition information panels, prioritizing products with minimal added sugars, unhealthy fats, and excessive sodium.

Prioritize Whole Foods: Base diets on unprocessed or minimally processed foods including fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds—foods your grandmother would recognize.

Prepare Meals at Home: Home cooking provides greater control over ingredients and portion sizes compared to consuming pre-packaged alternatives.

Limit Portion Sizes: If occasionally consuming UPFs, maintain portion awareness to prevent excess caloric intake.

Educate Your Family: Share knowledge about food processing and health risks with family members, establishing household norms supporting healthier food choices.

![]()

Conclusion: A Public Health Imperative

India stands at a critical juncture regarding its escalating non-communicable disease burden driven by ultra-processed food consumption. The 40-fold increase in UPF sales since 2006, coupled with doubling obesity rates and 10% diabetes prevalence, represents a public health emergency requiring urgent, comprehensive action. While individual dietary choices matter, the primary responsibility for addressing this crisis rests with policymakers, public health authorities, and the food industry.[4]

The scientific evidence is unequivocal: ultra-processed foods, characterized by high levels of added sugars, unhealthy fats, sodium, and artificial additives while being deficient in essential nutrients and fiber, directly contribute to obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and premature mortality. The mechanisms through which UPFs cause harm—metabolic dysregulation, chronic inflammation, gut dysbiosis, and endocrine disruption—are well-established and reproducible across diverse populations.[2]

India's experience echoes global patterns where rapid UPF market expansion precedes epidemic increases in diet-related NCDs. However, India also possesses opportunities to learn from international policy successes and implement evidence-based interventions before the NCD burden becomes even more catastrophic. Implementing comprehensive policies including front-of-pack warning labels, taxation, advertising restrictions, school food policies, and coordinated public health campaigns can effectively reduce UPF consumption and prevent millions of premature deaths.[6]

The path forward requires commitment from government, the food industry, healthcare providers, educators, and consumers—each playing vital roles in reversing India's NCD trajectory and ensuring healthier futures for current and future generations.

Post your opinion

No comments yet.