Understanding Influenza: The Disease and Treatment Rationale

The Burden of Seasonal Influenza

Influenza remains a significant public health threat worldwide, causing millions of infections annually, with complications including pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death, particularly in vulnerable populations including young children, elderly individuals, and those with chronic medical conditions. The economic burden of influenza extends beyond direct medical costs to include lost productivity, missed work and school, and healthcare system strain during peak flu seasons. Severe influenza complications can require hospitalization, intensive care admission, and mechanical ventilation support, underscoring the importance of prompt treatment, particularly in high-risk patients.[1]

When Antiviral Treatment Is Most Effective

Antiviral treatment for influenza is most effective when started within 48 hours of symptom onset, though some benefit may extend beyond this window, particularly in hospitalized and severely ill patients. Early treatment reduces symptom duration by approximately one day on average and, more importantly, appears to reduce the risk of serious complications including hospitalization, pneumonia, and mortality in high-risk patients. Treatment is recommended for patients with severe, complicated, or progressive illness; hospitalized patients; high-risk patients with uncomplicated illness; and those at risk for complications such as pregnant women, children younger than 2 years, and immunocompromised individuals.[1]

Influenza - Lung Care Foundation

A Day-by-Day Guide to Flu Stages

![]()

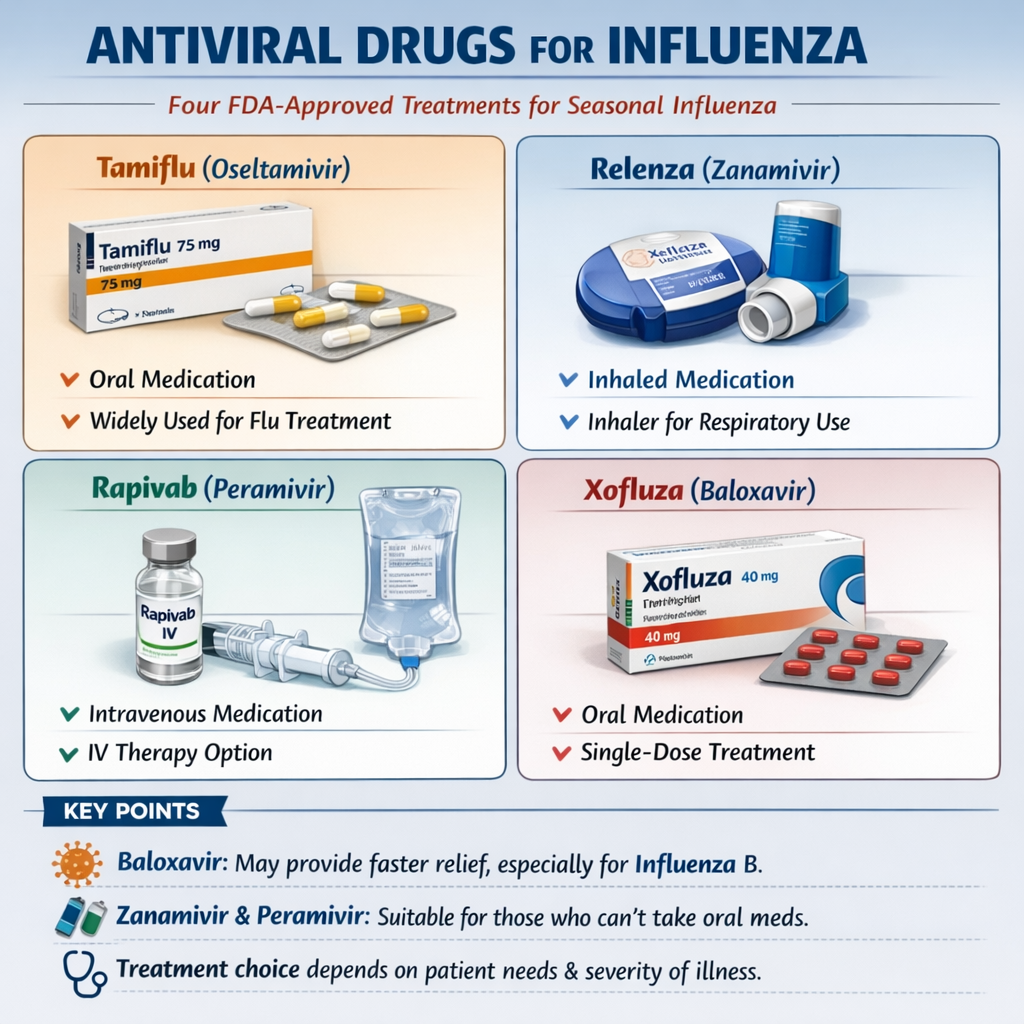

FDA-Approved Antiviral Medications: Complete Overview

1. Oseltamivir (Tamiflu): The Gold Standard and Most Prescribed Antiviral

Oseltamivir is an oral neuraminidase inhibitor that prevents viral neuraminidase—an enzyme on the influenza virus surface—from cleaving sialic acid receptors, thereby preventing viral release from infected cells and suppressing viral spread throughout the respiratory tract. The medication is taken orally as a capsule or liquid suspension, with a standard treatment course lasting five days. Oseltamivir is the most commonly prescribed influenza antiviral globally, accounting for more than 99% of influenza antiviral use in pediatric populations, owing to its wide availability, low cost, well-established safety profile, and FDA approval for treatment of children as young as 2 weeks old.[1]

Efficacy and Clinical Outcomes

In randomized clinical trials, oseltamivir treatment within 48 hours of symptom onset shortened symptom duration by approximately 0.75 days compared to placebo or standard care and was associated with reduced incidence of influenza-related complications and fewer antibiotic prescriptions. In hospitalized patients with severe influenza, oseltamivir treatment started within 48 hours after symptom onset resulted in shorter hospitalization duration compared to no antiviral treatment. Oseltamivir demonstrates efficacy against both influenza A and influenza B viruses, with protective efficacy of approximately 70-90% for chemoprophylaxis (preventive use) in individuals and households.[1]

The primary advantages of oseltamivir include decades of clinical experience documenting safety, widespread availability and relatively low cost, multiple formulations suitable for various patient populations, and approval for use across diverse age groups. The medication is appropriate for pregnant women, young children, and hospitalized patients. However, oseltamivir requires five days of twice-daily dosing, which can impact medication adherence, and gastrointestinal side effects including nausea and vomiting occur in 10-15% of patients, potentially complicating treatment in some individuals.[1]

Xofluza vs. Tamiflu: Differences and Similarities

2. Baloxavir Marboxil (Xofluza): The Single-Dose Innovation

Baloxavir marboxil represents a novel class of antiviral agents called cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitors that target a different viral protein than neuraminidase inhibitors—specifically the viral polymerase acidic (PA) protein essential for viral replication. This distinct mechanism provides advantages in specific clinical scenarios. The medication is administered as a single oral dose, substantially improving medication adherence compared to five-day courses required for other antivirals. Dosing is based on body weight, with typical doses ranging from 40 mg to 80 mg in adults.[1]

Efficacy and Clinical Outcomes

In comparative clinical trials, baloxavir produced faster reductions in infectious viral titers compared to oseltamivir for both influenza A(H3N2) and influenza B, with some studies demonstrating faster symptom improvement, particularly in patients with influenza B. A major clinical trial (CAPSTONE-2) comparing baloxavir with oseltamivir in 2,184 outpatients at high risk for complications found median time to symptom improvement was similar for the two drugs overall, but was statistically significantly shorter with baloxavir in patients infected with influenza B (74.6 vs 101.6 hours). Meta-analysis across 73 randomized trials found that baloxavir reduced symptom duration by a mean of 1.02 days compared to placebo—modestly superior to oseltamivir's 0.75-day reduction.[1]

Advantages and Specific Indications

The major advantage of baloxavir is the single-dose regimen, dramatically improving medication adherence and permitting straightforward post-exposure prophylaxis within 48 hours of exposure. For patients with influenza B, faster symptom improvement with baloxavir may provide practical advantages. The medication is active against neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant strains of influenza A and B, making it valuable in patients with resistant infections. However, baloxavir is not recommended for severely immunocompromised patients as monotherapy due to concerns that prolonged viral replication in such patients could lead to resistance emergence.[1]

3. Zanamivir (Relenza): Inhaled Alternative with Unique Delivery

Zanamivir is a neuraminidase inhibitor structurally similar to oseltamivir but delivered via oral inhalation using a handheld powder inhaler device, allowing direct delivery to the respiratory tract where influenza replication occurs. This localized delivery approach provides high drug concentrations at the site of viral replication while minimizing systemic absorption and associated side effects.[1]

Clinical Applications and Advantages

Zanamivir is particularly valuable for patients who cannot take oral medications or who experience gastrointestinal intolerance to oseltamivir. Additionally, inhaled zanamivir may be considered in patients with poor clinical response to oseltamivir, those with confirmed virus strains demonstrating oseltamivir resistance, and patients with gastrointestinal dysfunction requiring discontinuation of oral medications. The medication has demonstrated protective efficacy of approximately 70-90% for both pre-exposure and post-exposure chemoprophylaxis. Zanamivir also remains effective against neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant strains with specific mutations, making it valuable as salvage therapy when oseltamivir resistance emerges during treatment.[1]

Limitations and Special Considerations

A significant limitation is that zanamivir requires use of an oral inhalation device, which necessitates patient instruction and coordination, potentially limiting its use in very young children, elderly patients with cognitive impairment, or severely ill hospitalized patients who cannot effectively inhale the medication. Some patients experience bronchospasm (airway constriction) with inhaled zanamivir. Intravenous zanamivir formulations exist for patients unable to tolerate oral inhalation and are particularly valuable in critically ill patients, though clinical experience remains limited.

4. Peramivir (Rapivab): Intravenous Option for Special Populations

Peramivir is an intravenous neuraminidase inhibitor administered as a single 600 mg dose over 15-30 minutes for mild-to-moderate influenza, or as daily doses for hospitalized patients with severe influenza. The intravenous administration route eliminates absorption variability inherent with oral medications, making it particularly valuable for patients with gastrointestinal dysfunction, absorption disorders, or inability to take medications by mouth.[1]

Clinical Use in Specific Populations

Peramivir serves as an alternative to oseltamivir for hospitalized patients where enteral (oral or tube) drug administration is contraindicated, including those with severe nausea and vomiting, severe diarrhea, gastrointestinal surgical procedures, or altered mental status preventing safe oral medication administration. For patients requiring mechanical ventilation or those unable to swallow medications safely, peramivir provides a crucial alternative. A randomized clinical trial demonstrated that peramivir and oseltamivir produced similar time to fever alleviation in outpatient settings, indicating comparable clinical efficacy.[1]

A key limitation is that peramivir does not retain activity against influenza A(H1N1) viruses with specific neuraminidase mutations (NA-H275Y substitutions), limiting its utility in patients infected with resistant strains. Additionally, peramivir has shown reduced effectiveness in some immunocompromised populations, with limited clinical data available in specific high-risk patient groups.[1]

Antiviral drug - Wikipedia

Intravenous therapy - Wikipedia

![]()

Comparative Efficacy: Head-to-Head Analysis

Symptom Duration and Viral Clearance

Meta-analysis of pediatric patients comparing baloxavir and oseltamivir found that baloxavir resulted in statistically significantly shorter symptom duration (including shorter fever duration) compared to oseltamivir across influenza A and B subtypes, though the clinical significance of differences measured in hours remains modest. For hospitalized patients with severe influenza, the FLAGSTONE trial found no statistically significant difference in median time to clinical improvement between combination neuraminidase inhibitor plus baloxavir therapy versus neuraminidase inhibitor monotherapy (97.5 vs 100.2 hours).[1]

Individual Strain Susceptibility

While all four FDA-approved antivirals remain active against the majority of circulating influenza viruses (over 99% of recently tested strains show susceptibility to neuraminidase inhibitors and baloxavir), specific resistance patterns can influence medication selection. For patients infected with oseltamivir-resistant strains, zanamivir or baloxavir may be more appropriate. Conversely, for baloxavir-resistant strains, neuraminidase inhibitors retain efficacy.[1]

For prevention following exposure, oseltamivir, zanamivir, and baloxavir all provide approximately 70-90% protective efficacy against laboratory-confirmed influenza when administered within 48 hours of exposure. Post-exposure prophylaxis reduces symptomatic influenza risk in high-risk individuals and household contacts of infected persons. Meta-analysis of 33 trials demonstrated that prompt post-exposure prophylaxis with any of these three agents significantly reduces risk of symptomatic seasonal influenza in patients at high risk for severe disease.[1]

![]()

Combination and Sequential Antiviral Therapies

When Combination Therapy Is Considered

For severely immunocompromised patients or those with severe illness, combination therapy pairing a neuraminidase inhibitor with baloxavir may offer advantages over monotherapy through additive antiviral effects and reduced risk of resistance emergence. The FLAGSTONE trial found that among patients for whom paired pre- and post-treatment samples were available, treatment-emergent neuraminidase inhibitor substitutions occurred less frequently in the baloxavir plus neuraminidase inhibitor group versus neuraminidase inhibitor monotherapy group (2% vs 4%). However, triple therapy combinations (oseltamivir, ribavirin, and amantadine) demonstrated synergistic activity in laboratory studies but failed to produce clinical benefits in immunocompetent patients and are not routinely recommended.[1]

For patients with poor clinical response to initial antiviral therapy, switching to alternative agents or adding complementary medications under specialist guidance may be warranted. Healthcare providers should consider resistance testing for patients who develop confirmed influenza despite prophylaxis or fail to improve on initial antiviral treatment. Sequential therapy strategies require individualized assessment and specialist involvement in most cases.[1]

![]()

Side Effects and Safety Considerations

Tolerability Across Different Antivirals

Oseltamivir most commonly causes gastrointestinal side effects including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, occurring in 10-15% of patients, with nausea being the most frequently reported symptom. The incidence of gastrointestinal side effects is similar across age groups and treatment indications. Baloxavir demonstrates comparable overall safety and tolerability to oseltamivir, with similar incidence of adverse events across both agents. Gastrointestinal symptoms also occur with baloxavir but are less frequent than with oseltamivir in some studies.[1]

Zanamivir's inhaled delivery minimizes systemic absorption, generally resulting in fewer systemic side effects compared to oral antivirals. However, inhaled zanamivir can cause bronchospasm (airway constriction), particularly in patients with underlying airway disease including asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patients with reactive airway disease should have bronchodilators available when using inhaled zanamivir.[1]

Peramivir, administered intravenously, typically demonstrates good tolerability with systemic side effects similar to or fewer than oral antivirals. The intravenous route avoids gastrointestinal toxicity altogether.[1]

Serious adverse events are rare across all approved antivirals, with reported incidence below 5% in most clinical trials. Events reported include psychiatric symptoms (behavioral changes, hallucinations, delirium) more commonly documented with oseltamivir in adolescents and young adults, though whether these represent true drug effects versus symptoms of severe influenza remains debated. Seizures have been very rarely reported with oseltamivir use, particularly in patients with underlying seizure disorders or at high risk for convulsions.[1]

Special Populations and Contraindications

All approved antivirals are considered safe in pregnancy, with oseltamivir preferred based on extensive pregnancy safety data. Neuraminidase inhibitors are approved for use in children as young as 2 weeks old (oseltamivir) or 7 years old (zanamivir), whereas baloxavir is approved only for children weighing at least 40 kg. Live-attenuated intranasal influenza vaccine should not be administered within specific timeframes after antiviral use due to potential suppression of vaccine effectiveness.[1]

![]()

Resistance and Emerging Concerns

Over 99% of recently circulating influenza virus strains tested by the World Health Organization maintain susceptibility to neuraminidase inhibitors and baloxavir, indicating that resistance remains uncommon in the general population. However, reduced susceptibility of some influenza A(H1N1) viruses to oseltamivir or peramivir has been detected in specific geographic regions and patient populations, necessitating surveillance and awareness.[1]

Risk Factors for Resistance Development

Baloxavir monotherapy in severely immunocompromised patients is not recommended because prolonged viral replication in such individuals could select for resistant strains. Similarly, extended treatment courses or high-dose therapy in immunocompromised populations require careful consideration and monitoring for resistance emergence. Resistance testing should be performed for patients who develop confirmed influenza despite prophylaxis or fail to improve on initial antiviral treatment, guiding selection of alternative agents.[1]

![]()

Special Situations: Treatment Considerations by Population

Hospitalized and Severely Ill Patients

For hospitalized patients with severe influenza, oseltamivir remains the first-line agent, with intravenous zanamivir or peramivir as alternatives when oral administration is contraindicated. Early treatment within 48 hours of symptom onset is particularly important in this population, as antiviral therapy reduces hospitalization duration and appears to prevent serious complications.[1]

Immunocompromised patients require specialized treatment considerations, as prolonged viral replication and higher viral loads increase risks of complications and resistance emergence. Neuraminidase inhibitors are first-line treatments, with baloxavir combined with neuraminidase inhibitor therapy potentially offering advantages. Extended treatment courses beyond standard durations may be considered for severely immunocompromised patients, requiring specialist consultation.[1]

Pregnant Women and Young Children

Oseltamivir is preferred for treatment of pregnant women, based on substantial safety data from pregnancy registries and observational studies. Young children (younger than 2 years) face elevated risks of severe influenza complications, making antiviral treatment particularly important in this population. Oseltamivir is approved for use in infants as young as 2 weeks of age, making it the preferred agent in very young children.[1]

Elderly patients frequently have comorbid medical conditions and take multiple medications, requiring careful consideration of drug interactions. Oseltamivir remains the preferred agent, though single-dose baloxavir may improve adherence in some elderly patients with complex medication regimens.[1]

Focus: COVID-19 pill developers aim to top Merck, Pfizer ...

![]()

Prophylactic Use: Prevention of Influenza Infection

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Indications

Post-exposure prophylaxis (preventive antiviral treatment after exposure to someone with confirmed influenza) should be considered within 48 hours of exposure for persons at very high risk of complications who have not received annual influenza vaccination, received vaccination within the previous 2 weeks, or might not respond to vaccination adequately, or when the vaccine-strain match is poor. Persons at very high risk include elderly individuals, those with chronic medical conditions, pregnant women, young children, and immunocompromised patients.[1]

Prophylactic Efficacy and Recommendations

Oseltamivir, zanamivir, and baloxavir are all FDA-approved for chemoprophylaxis, with post-exposure prophylaxis courses lasting 10 days for oseltamivir and zanamivir, and requiring a single dose of baloxavir within 48 hours of exposure. Meta-analysis demonstrates that prompt post-exposure prophylaxis with any of these agents reduces symptomatic influenza risk by 58-89% in household contacts and individuals following exposure. For institutional influenza outbreaks, the CDC recommends chemoprophylaxis with oseltamivir or zanamivir for at least 2 weeks, continuing for up to 1 week after outbreak resolution.[1]

![]()

Practical Guidance for Patients and Providers

When to Seek Antiviral Treatment

Patients should seek medical evaluation within 48 hours of symptom onset if they are at high risk for complications, including those with severe symptoms, chronic medical conditions, pregnancy, age extremes, or immunocompromising conditions. Early medical evaluation enables timely antiviral treatment initiation.

Medication Selection Considerations

Oseltamivir remains the initial choice for most patients due to extensive safety data, availability, low cost, and approval across diverse age groups. Baloxavir may be preferred when single-dose convenience is important or for influenza B infections where faster symptom improvement may provide advantages. Zanamivir is appropriate for patients with gastrointestinal intolerance or absorption disorders. Peramivir is reserved for hospitalized patients unable to take oral or inhaled medications.[1]

The 48-hour window from symptom onset is critical, as antivirals initiated within this timeframe provide maximum benefit for symptom reduction and complication prevention. Patients experiencing flu symptoms should seek prompt medical evaluation rather than delaying treatment.[1]

![]()

Conclusion: Empowered Treatment Choices for Influenza

While Tamiflu (oseltamivir) has been the default flu antiviral for decades, four FDA-approved antivirals now offer patients and healthcare providers multiple evidence-based treatment options, each with distinct advantages suited to different clinical scenarios and patient populations. Understanding these alternatives empowers informed decision-making: oseltamivir remains the gold standard for most patients, but baloxavir's single-dose convenience and potentially faster symptom relief for influenza B make it attractive in specific situations. Zanamivir's inhaled delivery and avoidance of gastrointestinal side effects benefit patients with absorption issues or intolerance to oral medications. Peramivir's intravenous administration is essential for hospitalized patients unable to take oral or inhaled medications.[1]

The evolving understanding of these medications' comparative efficacy, optimal use in specific populations, and resistance patterns continues to inform clinical practice guidelines. For patients with severe illness, at high risk for complications, or in whom initial antiviral therapy fails, specialist consultation can guide selection of alternative agents or combination therapy approaches. Ultimately, prompt medical evaluation within 48 hours of symptom onset and shared decision-making regarding medication selection optimize outcomes for patients with influenza, reducing symptom duration, preventing serious complications, and supporting faster return to normal functioning.[1]

![]()

Citations:

CDC - Treating Flu with Antiviral Drugs (2025); Medical Letter - Antiviral Drugs for Seasonal Influenza for 2025-2026 (2025); PMC - Antiviral strategies against influenza virus (2025); Academic OUP - Influenza Antivirals for Prevention and Treatment (2025); PMC - The current state of research on influenza antiviral drug development (2023); PMC - Influenza Antivirals: Do We Need More Evidence (2025); UK Government - Guidance on use of antiviral agents for treatment and prophylaxis (2025); Frontiers in Microbiology - Comparison of the efficacy and safety of baloxavir versus oseltamivir (2025); PLoS ONE - Use of Neuraminidase Inhibitors for Rapid Containment of Influenza (2014)[1]

Post your opinion

No comments yet.